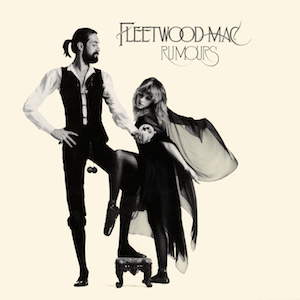

Love, Loss, and Lots of Cocaine

Released: February 4, 1977

If you’ve ever wondered what happens when two couples break up, another relationship crumbles, and everyone involved has to keep working together while having access to unlimited studio time and a blizzard of cocaine, well, “Rumours” is your answer. The miracle isn’t just that this album got made—it’s that it turned out to be one of the greatest albums ever recorded.

“Second Hand News” kicks things off with Lindsey Buckingham channeling his frustration into what might be history’s most upbeat kiss-off. The production is immaculate, with layers of acoustic guitars creating a rhythmic foundation that makes heartbreak sound like a party you actually want to attend.

“Dreams” follows, with Stevie Nicks delivering a masterclass in ethereal revenge. Only Stevie could make a song about romantic devastation sound like it was written by a mystical wizard floating on a cloud. The track’s groove is so hypnotic it could probably solve international conflicts if played at the right diplomatic summit.

“Never Going Back Again” serves as Buckingham’s acoustic guitar flexing session, proving that sometimes the best way to deal with relationship trauma is to play so many intricate fingerpicking patterns that your ex’s head spins. The song is brief but packs more technical prowess into two minutes than most guitarists manage in their entire careers.

Christine McVie provides “Don’t Stop,” the album’s most optimistic moment, which is a bit like being the happiest person at a funeral. The song would later become Bill Clinton’s campaign theme, proving that even politicians occasionally have good taste in music.

“Go Your Own Way” might be the most passive-aggressive use of harmonies in rock history. There’s something beautifully twisted about having your ex sing backing vocals on a song about how terrible they are. The drum fill leading into the final chorus should be in a museum somewhere.

“Songbird” offers a moment of gentle reprieve, with Christine McVie proving that at least one person in Fleetwood Mac could write about love without needing an exorcism afterward. The song’s sincerity almost feels like it got lost and wandered in from another album entirely.

“The Chain,” the only song credited to all five members, is what happens when shared trauma creates accidental genius. That bass line in the bridge could raise the dead, or at least raise enough questions about what exactly was in that studio coffee.

“You Make Loving Fun” is Christine McVie’s ode to her new love (who wasn’t in the band, thankfully—there were enough relationship dynamics to keep track of already). The irony of recording this while her ex-husband John played bass on it is the kind of thing you couldn’t make up if you tried.

“I Don’t Want to Know” and “Oh Daddy” keep the emotional rollercoaster rolling, before “Gold Dust Woman” closes the album with Stevie Nicks at her most mystically menacing. It’s the sound of the 1970s California music scene eating itself alive in the most beautiful way possible.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (5/5 stars)

Final Thoughts: “Rumours” is probably the only time in history that relationship dysfunction produced something that actually made the world better. Its only flaw might be that it set an unrealistic standard for breakup albums—not everyone has access to multiple genius songwriters, world-class studios, and enough chemical enhancement to power a small city. The album’s legacy is a testament to the power of turning personal chaos into professional triumph. It’s also proof that sometimes the worst thing for your personal life can be the best thing for your art. Just don’t try this at home, kids—having your entire band engage in romantic musical chairs isn’t a recommended career strategy. But if you do find yourself in the middle of romantic turbulence, at least you’ll have the perfect soundtrack.