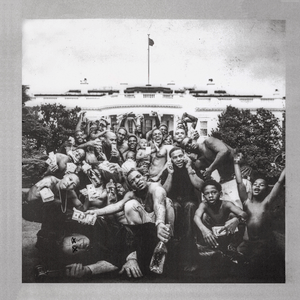

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy: When Ego Achieves Its Final Form

Look, let’s address the elephant-sized ego in the room right off the bat – Kanye West might be the most insufferable human being to ever grace a VMAs stage (and that’s saying something). But sometimes, just sometimes, an artist’s messiah complex actually delivers something approaching divine. “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” is what happens when someone’s god complex accidentally produces something godlike.

The album opens with “Dark Fantasy,” and immediately you realize this isn’t just another hip-hop record – it’s more like hip-hop’s answer to a Broadway musical directed by Stanley Kubrick while high on baroque architecture. When that choir kicks in asking “Can we get much higher?” the answer is clearly no, because we’re already in the stratosphere, and Kanye’s just warming up.

Then “Gorgeous” drops, and Kid Cudi’s hook sounds like it was recorded in some alternate universe where melancholy is actually a physical substance you can smoke. Kanye’s verses here are sharper than a surgeon’s scalpel, proving that when he’s not busy tweeting about being the next Walt Disney, he can actually rap his absolute ass off.

“POWER” might be the most accurate sonic representation of megalomania ever recorded. It’s like someone turned a god complex into sound waves. That King Crimson sample isn’t just a flex – it’s Kanye basically saying “Yeah, I can make progressive rock work in hip-hop, what are YOU doing with your life?”

And then there’s “All of the Lights” – a song so maximalist it makes Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound look like a garden fence. Rihanna’s chorus sounds like it was recorded in the midst of a supernova, while that horn section could wake the dead and make them dance. It’s utterly ridiculous, completely over-the-top, and somehow absolutely perfect.

“Monster” is where things get really interesting. Nicki Minaj’s verse isn’t just great – it’s the kind of performance that makes you want to throw your phone into the ocean and never attempt to rap again. Even Jay-Z showing up and comparing himself to a sasquatch somehow works, because at this point, why not?

“So Appalled” is basically a luxury rap fever dream, while “Devil in a New Dress” might be the most beautiful thing Rick Ross has ever been adjacent to. That guitar solo comes in like it got lost on its way to a Pink Floyd album and decided to stay because the accommodations were nice.

“Runaway” is the centerpiece, and good lord, what a piece it is. It’s nine minutes of the most beautiful self-awareness about being an absolutely terrible person ever recorded. That distorted outro sounds like what regret would sound like if it learned to sing – assuming regret took AutoTune lessons first.

But here’s the thing – for all its undeniable brilliance, this album is also completely bonkers. It’s like watching someone build the Sistine Chapel while occasionally stopping to eat the paint. The production is maximal to the point of absurdity, the lyrics swing between profound and profoundly narcissistic, and the whole thing feels like it’s constantly on the verge of collapsing under the weight of its own ambition.

Rating: 4.8 out of 5 Solid Gold Ego Trips 👑

Peaks:

- Production so lush it makes the Gardens of Babylon look like a window box

- Verses that range from hilarious to heartbreaking, sometimes in the same line

- Features list that reads like a hip-hop infinity gauntlet

- Actually earning its own grandiosity

Valleys:

- Occasionally disappears up its own artistry

- Some interludes that feel like Kanye just couldn’t bear to cut anything

- The lingering knowledge that this album probably made Kanye even more Kanye

Final Thought: “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” is like watching someone successfully juggle chainsaws while reciting Shakespeare and doing quantum physics – it shouldn’t work, it’s definitely dangerous, and you kind of want to tell them to stop, but you also can’t look away. It’s an undeniable masterpiece created by an occasionally unbearable mastermind. In the end, it’s proof that sometimes the line between genius and madness isn’t just thin – it’s nonexistent. And sometimes, just sometimes, that’s exactly what we need.

P.S. – The fact that this album came with a short film that looks like what would happen if Matthew Barney directed a hip-hop video is just chef’s kiss perfect. Because of course it did.